The Cinema will Save Us

At a time of unprecedented global division, a record Memorial Day box office shows us the way forward.

It’s hard to not keep flashing back to Ted Sarandos’ recent dismissal of moviegoing as a heralded pastime, even after I mocked it earlier this month. That’s because for all of Sarandos’ turgid corporate sourpussiness in declaring filmgoing “an outmoded idea for most people” and crowning Netflix as Hollywood’s new savior, most audiences over the Memorial Day weekend chose to watch no Netflix movies and instead stampede into movie theaters in such record numbers that with Memorial Day itself yet to come, the holiday weekend has already been forecast as the biggest Memorial Day haul in box office history, officially dethroning 2013’s. That’s largely on the back of Disney’s live action Lilo & Stitch, which is posting the best Memorial Day weekend numbers of any such opener in history exactly one year after Furiosa and Garfield combined for one of the worst, leading many to declare the holiday, if not Hollywood itself, officially dead. That Tom Cruise is coming in second with similarly historic numbers for Mission: Impossible The Final Reckoning speaks to what an astonishing difference a year makes.

This all comes on the heels of a lackluster Cannes Film Festival where the general take-away from the likes of expert industry analyst

is that the middle-ground is struggling while at the top end, to use Follows’ words, “there was no shortage of money for star-driven or award-contending packages,” reflecting, as Follows sees it, “a growing reluctance among buyers even to consider projects that lacked clear marketing hooks or theatrical potential.”Film buyers want movies that can be marketed to general audiences and shown in theaters. They don’t want Netflix movies. Streaming is not the future.

A statement that unequivocal shouldn’t need me to serve up a lay translation, but I’ll do it anyway for emphasis: Film buyers want movies that can be marketed to general audiences and shown in theaters. They don’t want Netflix movies. Streaming is not the future.

I previously laid out the data that shows theatrical release movies dominant on streaming precisely because they carry the prestige factor of having been released in theaters — no point in doing so again. Audiences have once again spoken loudly and clearly, as they did during the Barbenheimer phenomenon two years ago, that movie theaters are going nowhere. When audiences abandon theaters, it’s not because they no longer value the experience — it’s because the available inventory of movies isn’t living up to their expectations of that experience. That’s a far cry from the dynamic of streaming where, as

just astutely observed, “You’re not the audience anymore.” In her very observant essay, Bateman asserts that streaming viewers are really no longer the relevant audience because they “are no longer the financial end-game.” While I don’t entirely buy into the framework she outlines for justifying that conclusion, the difference between her take and mine is one of minutiae. The relevant point is that streaming content — like the increasingly ubiquitous social media content that is rapidly displacing it — is not designed to meet the expectations of the audience. It’s designed to meet the expectations of corporate executives whose goals are to capture eyeballs without necessarily touching hearts. In a world overburdened by digital noise, streaming merely adds to the deafening cacophony while theatrical films seek to furnish us a refuge from and an antidote to the noise. While streaming and social video work to keep us cooped up in front of our personal screens deliberately cut off from other humans for whom each digital experience has been expertly and individually curated, theatrical films demand that we leave those screens behind and join with those other humans in a shared experience that defies any attempt at curation. Simply put, streaming sees economic opportunity in our division, where theatrical sees economic opportunity in our commonality.At the same time, streaming and theatrical, contrary to the media’s attempt to invent some kind of a zero sum competition, are not at odds. This is not a fight over which will ultimately prevail for the attention of the world’s audiences because the two things play fundamentally different roles in people’s lives. It’s been over seventy years since Swanson brought us TV dinners, and nearly sixty years since Tappan gave us home microwaves but people still make time to go out to eat. If anything, the ubiquitousness of microwavable dinners has elevated the restaurant experience to where we now have reality TV series that celebrate precisely what goes on in restaurant kitchens. The fact that theatrically-released movies dominate streaming popularity should be no more surprising than the fact that the most popular frozen dinners bear the names of famous restaurateurs like Gordon Ramsay and Wolfgang Puck. In both cases, the collective experience is validating — we respect the branding because it has been ordained by our communal decisions.

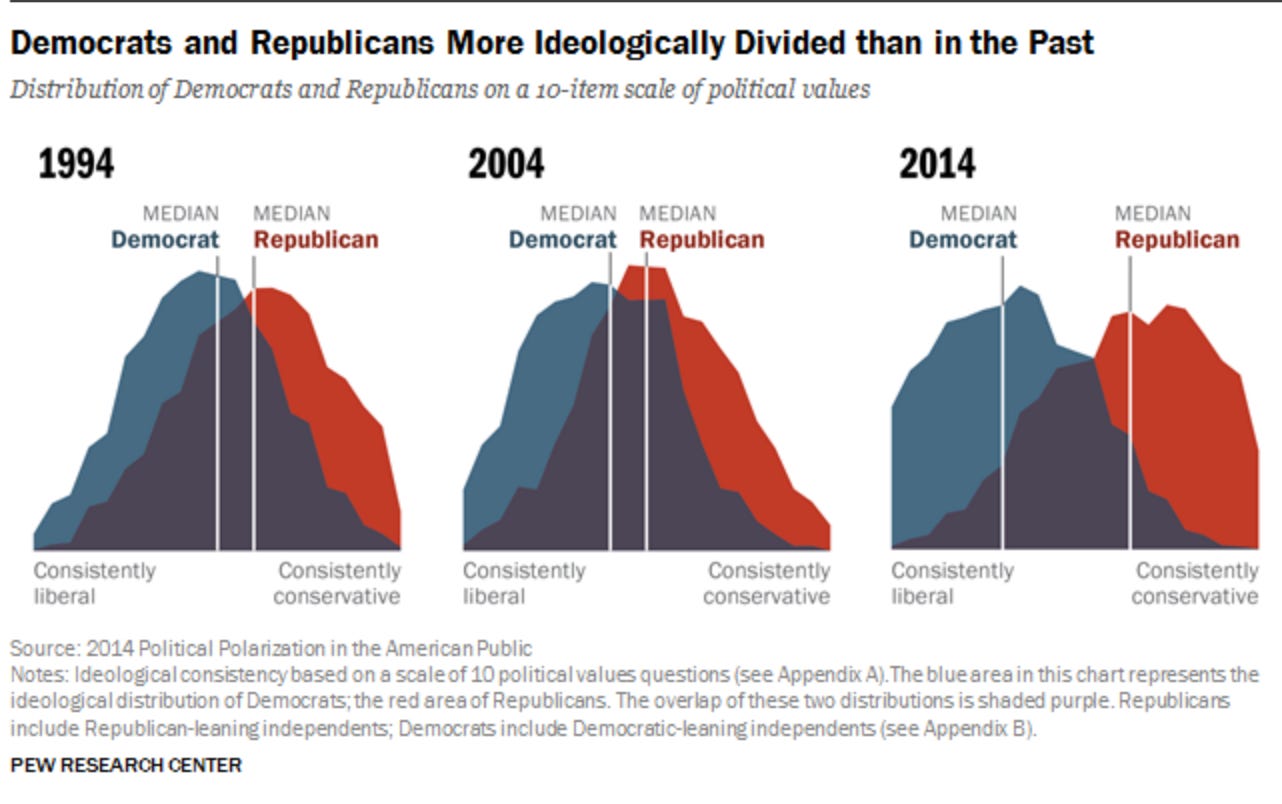

Which brings us to the world in which we live. If we were to ignore things like box office and focus exclusively on bills pending before congress and state legislatures, or the hellscape of conflicting court rulings on any number of cultural issues, not to mention the even greater chaos enveloping nearly every developed nation on the planet, we might imagine a very dark future that exceeds even that of George Miller’s Mad Max universe. Pew already identified this trend a decade ago by demonstrating a more volatile divergence among the American political tribes between 2004 and 2014 than in any prior decade stretching back over a century. Recent Pew data confirms that this trend has, tragically, continued, with partisans growing more untrusting of each other over the decade since.

As with most things in life, perspective is everything. To make sense of these numbers one need simply overlay them with Internet and social media usage data. Between 2005 and 2025 Internet use by Americans alone has swollen from 15% of the population to 68%. In just ten years, global social media use has more than doubled, from 2.08 billion users in 2015 to 5.24 billion today. Correlation may not be causation in general principle, but the correlation here is too obvious to dismiss. In the pre-digital era, whatever our general disagreements on matters of politics, religion, ethics, economics or culture, we still had to live in the same reality. We all watched Cronkite and Carson, read the local paper of record and crossed paths at the same non-partisan grocery stores and post offices. Today, Internet and social media democratization of every aspect of our lives makes it possible to curate a customized personal reality entirely divorced from that of the people next door. Thanks to Amazon and Instacart, we no longer have to leave the house to shop at the same grocery store. Thanks to social media, trips to the post office are largely relegated to shipping holiday packages. Depending on your chosen cultural or political tribe, you may regularly tune in to MSNBC while your neighbor watches Fox News. For all the validation that you receive from your post on X, your neighbor is getting similar validation on BlueSky. In a world where you no longer need to interface with your neighbors in the same external reality — where you can disappear down a curated reality of your choosing and construction without ever leaving the confines of your own couch — the inevitable end result is digitally-induced tribalism and division.

One can fairly surmise that among the audiences that flocked to both Lilo & Stitch and Mission: Impossible The Final Reckoning include both those who voted for President Trump and those who voted for Vice President Harris… all of them breathing the same air in the same theaters on the same weekend, laughing and crying together…

Numbers like this weekend’s box office results, however, suggest that such division is clearly more cosmetic than media reports would have us believe. One can fairly surmise that the audiences that flocked to both Lilo & Stitch and Mission: Impossible The Final Reckoning include both those who voted for President Trump and those who voted for Vice President Harris, those who are atheists and those who are believers, those who eat beef and those who are vegan, those who are comfortably well-off and those who scrape by paycheck to paycheck, those who consider themselves ethnic and sexual minorities, and those who do not — all of them breathing the same air in the same theaters on the same weekend, laughing and crying together, gritting their teeth and gripping their theater armrests together because they all still value what they have in common more than what they do not.

It would be easy to be cynical about the fact that two years after Barbenheimer, we’re right back to franchise films — a live-action remake of a 23-year-old Disney animated favorite and the eighth and final installment of a nearly thirty-year-old action franchise based on a nearly sixty-year-old TV series, starring a 62-year-old movie star. But the demographic numbers tell a different story — audiences of all ages and backgrounds went to both films (though Mission: Impossible skewed more male and Lilo & Stitch more female); and Mission: Impossible The Final Reckoning once again delivered the same key demographics that helped end the COVID-19 box office slump with Top Gun: Maverick three years ago today. A whopping 29% of the final Mission: Impossible installment’s audience is over the age of 55, while 62% are over 35. That’s an incredible eight percentage point gain over the 54% over-35 figure that bought tickets for Top Gun: Maverick. A demographic which, we are repeatedly told, is in “no rush” to go back to movie theaters.

That may be true generally speaking — but for the right film, they’ll rush to fill theater seats as eagerly as they did when they were in their teens and twenties.

That is why theaters matter. That is why theaters will never go away. That is why the cinema will save us.